In the wake of Florida’s House Bill 1557, aka the “Don’t Say Gay” bill, it is more important than ever that we share examples of queer joy. Lydia Conklin’s debut story collection Rainbow Rainbow does just that, entering boldly as a fearless exploration of the many facets of LGBTIA++ identity and as a beautiful reminder of the ways that queer joy can exist within a complex space. Their stories provide both a rare opportunity for LGBTQIA++ individuals to be lovingly depicted in literature and also a deep dive into the more liminal and uncertain queer identities that are not typically represented in media.

The collection includes ten stories with a range of characters, from pre-adolescents finding words to describe their sexuality, to a sex-addicted Midwestern librarian, to a nonbinary writer experiencing intimacy during the height of the COVID pandemic. The characters—some queer, some trans, some gender-nonconforming—are raw and fully embodied. Both their joys and their struggles are experienced by the reader in relation to their abilities to live freely in their bodies and to love how and who they want.

Conklin succeeds in their ability to depict uncertainty and self-exploration. Each story features a character undergoing a period of self-discovery, oftentimes on the eve of a significant transition. Characters of all ages yearn not just to be seen and understood by others but also to truly see and understand themselves. There is no single moment of transcendent self discovery, but rather a more realistic journey of what it means to constantly choose to be our fullest selves and to choose joy and resilience over passivity. This is most evident in the stories that explore transition. “Pink Knives,” “Sunny Talks,” and “Boy Jump” all center characters who are transgender and navigating how disclosing or seeking to live in their true identities may affect their interpersonal relationships.

In “Pink Knives,” the unnamed narrator describes a final fling before intending to undergo top surgery the next day. This bodily encounter is haunted by the narrator’s wonderings of whether their girlfriend will forgive them, not for the intimacy itself—their relationship is agreeably open— but rather for the details of this intimacy. While the narrator has never allowed their girlfriend to appreciate the curves of their body, and in fact worries if the girlfriend will forgive them for their surgery, they allow this near stranger to explore the curves of their chest in recognition that they will soon be gone. The messiness of this encounter and the fears that it surfaces are premonitions of messiness in the narrator’s relationships to come.

Differences in generational experiences of queer identity are at the heart of “Sunny Talks,” a story about an older adult who chaperones their nephew at a Gen Z conference for transgender youth while grappling with their own unshared desire to live between genders. The conference helps both child and adult to recognize the ways in which shared online communities can be beautiful and supportive but also toxic and drama-laden. The story suggests that maybe the ways in which we are seen, understood, and protected by our loved ones is most important, not the ways in which we present ourselves physically or the ways in which strangers might perceive us. The narrator’s maturity also provides a solemn reminder of the many people, particularly older adults, who lacked or still lack the support to live as their true selves. The story reverberates with the question: how many lives could be made more joyful if they were just given permission to be?

In “Boy Jump,” a transgender man in his thirties contemplates while abroad in Poland how to tell his girlfriend about his true identity and his desires to transition. As part of his tour of Poland, he is encouraged to take a dive at a popular outdoor swimming hole, forcing him to grapple with fears of both his emotional and physical wellbeing.

“A straight white man—that was my future. Trundling around pretending to be Jewish to steal a bit of pseudo-minority status. I’d turn invisible, privileged, easy in the world. Who would I be when I wasn’t exactly me anymore?”

“Boy Jump” is a reminder that transitioning is not just a physical journey but a deeply emotional and nuanced one , and a relearning of how to navigate both interpersonal relationships as well as a new set of societal expectations and norms. The narrator in “Boy Jump” takes not only a physical dive off a cliff, but also a metaphorical one into a profoundly new phase of life.

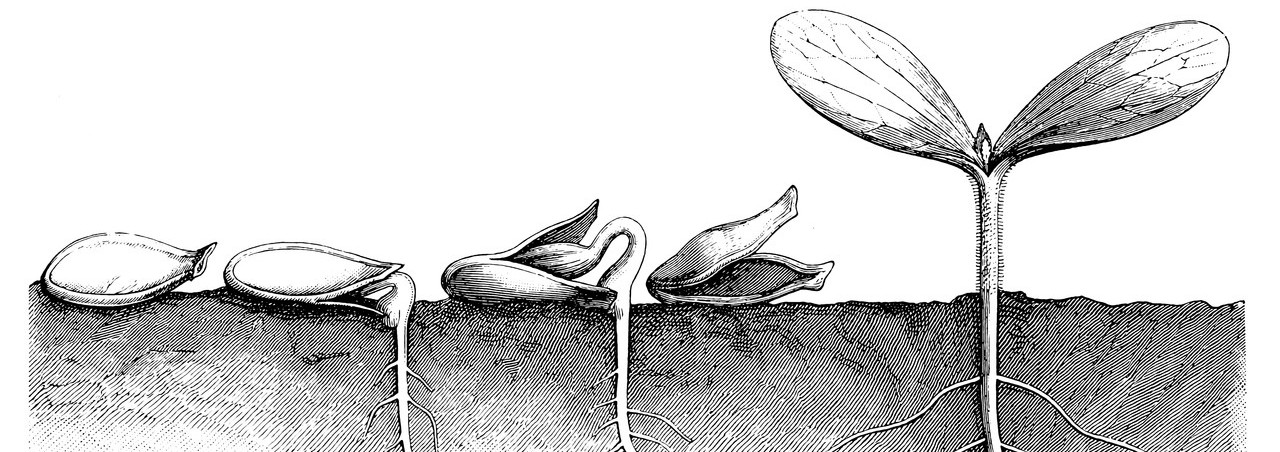

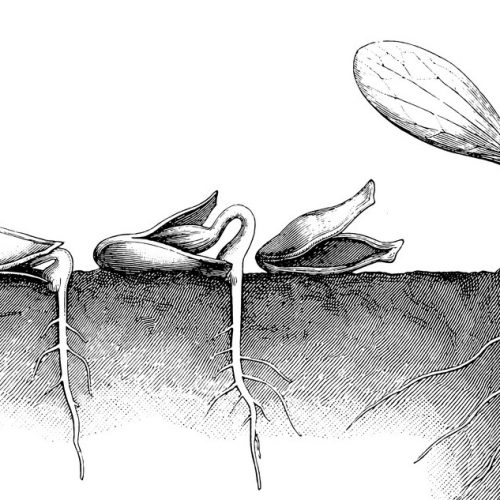

Conklin is a master of craft with an uncanny ability to create collective conversation on the joys, awkwardness, struggles, and beauty of finding and sharing one’s own identity. Their prose is bold yet exacting, often felt physically, both through considerate descriptions of the body and through metaphoric language that recalls physical sensations ( “My blood knifes again”). Their manipulation of language is reminiscent of Love in the Big City, written by Sang Young Park and translated by Anton Hur, conversational yet stirring, while the content of Conklin’s stories evokes the mundane beauty and power of Lydia Davis. The content of Rainbow Rainbow is heavy and meaty, but like life itself, it is dotted with moments of levity: a hand held, dreams of children, the feeling of being at home in one’s own body and skin. Like breadcrumbs leading to a promise of something greater, these small moments demand to be acknowledged and collected, providing reminders of the ways that beauty and joy shape what it means to be human.

Rainbow Rainbow is both representative and transcendent, providing a voice to the LGBTQIA++ community while simultaneously describing the universally intimate social struggles of being human. As both a reminder of the collection’s title and of the universal symbol of pride, rainbows appear throughout, first as an overwrought cosmically-colored cocktail and then later as the name of a fibbed childhood band that “made other girls gay.” As explained by the fibber in question:

“The name of the band [Rainbow Rainbow]… symbolized two people side-by-side. The people, who were incidentally girls, would eventually merge into one rainbow, or girl, but for now were separate ribbons of color, quivering together in the lonely sky.”

We live in a time of growing political and social polarization. The passing of laws targeting queer communities makes it increasingly clear that we are failing to listen to one another, failing to act with love and kindness, and failing to recognize each other’s human rights to live freely and fully. Rainbow Rainbow demands that we pause and take a look at each other, that we see the many shades of individuality as part of something beautiful and essential. If it’s not a stretch to say that each story in the collection is a separate ribbon of individual experience, then perhaps each reading of Rainbow Rainbow will bring us one step closer to merging into a single rainbow of collective joy and seeing.

Available now at Bookshop

Available now at Bookshop

Lauren Bo

Lauren Bo is a half-Taiwanese writer of fiction and poetry and reviewer of works by AAPI and Asian diasporic writers and of international works that have been translated into English. Her writing has been published by or is forthcoming with World Literature Today, Asymptote, The Cosmos Book Club, and My French Life Magazine. She is an inaugural member of Feminist Press' Young Feminist Leaders Council and lives in St. Louis with her husband and bunnies.