The radicle of Hala Alyan’s writing career sprouted in the sixth grade, after the first full book she ever read. In this interview, Hala and I explore this genesis and discuss the various roots and branches her writing has developed since. It includes four award-winning poetry collections and two stunning novels, the most recent of which is The Arsonists’ City, a rich family story, a personal look at the legacy of war in the Middle East, and an indelible rendering of how we hold on to people and the places we call home (out March 2021, by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt). Hala is a generous writer, and I use this adjective knowing well that all writing is laborious. In her newest novel, the generosity comes out in descriptions, and in the thought-provoking tangents within narration. She is giving, too, of her time and energy, willing to engage in conversations about art-making and the writerly existence during an especially busy time in her life: the month of her new novel’s launch, a week after the passing of her grandfather, in between travel, and soon after enduring multiple miscarriages. In learning about Hala through her words, I hope you are as compelled as I to spend some time with her writing.

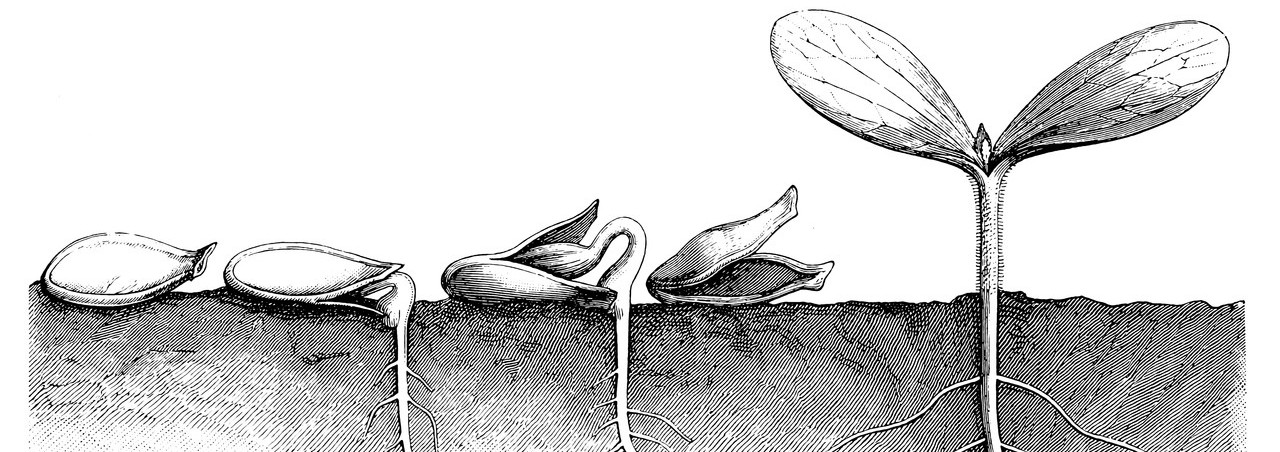

~ Basmah Sakrani, Radicle Interviewer

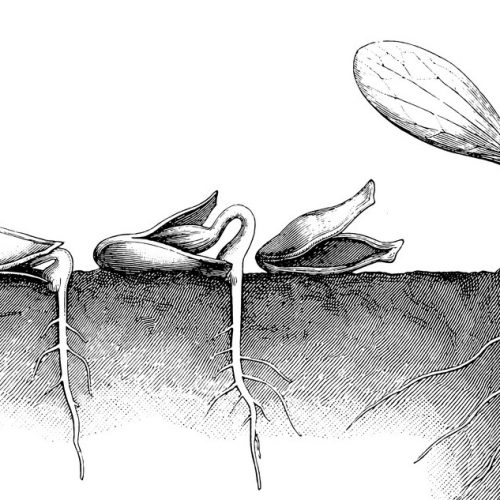

Basmah Sakrani: In botany, the radicle is the primary root, the first organ to appear when a seed germinates. It grows downward into the soil, anchoring the seedling and secondary roots grow laterally from it. What is the radicle of your writing career?

Hala Alyan: The radicle of my writing career was the first chapter book I read when I was in sixth grade. I was always ahead of my reading grade so my father got me the great illustrated classics and I think the radicle of my writing were those years in school when I would read these books and, to the delight of my father, recount them and answer his questions about them. It felt like a beautiful bonding moment and his face would just light up with joy and there was something in seeing how happy it made him that really bolstered my own delight in reading. Seeing how happy stories could make people made me want to tell stories.

Basmah Sakrani: What would you consider to be your breakthrough piece of writing and how did it come to you?

Hala Alyan: I guess it depends on how we are defining this. If breakthrough is commercial success, literary recognition, and money, then I would say it happened with my first novel, Salt Houses, just because there is a larger audience for fiction than there is for poetry. But here I’m also thinking about the first-ever thing that got published through independent submission. I was 22, living in New York, and I got a poem accepted in The Dirty Napkin, and it was a very cool publication. They have you write your poem on an actual napkin and send it in. The poem was called “gemini,” and that was really a breakthrough for me on a personal level because I sent it out into the world, and somebody wanted it.

Basmah Sakrani: In a recent book club interview, you mentioned that the inspiration for The Arsonists’ City occurred in a vivid dream of a Syrian woman coming of age in 1970s Damascus. It feels very much like this dream was the radicle of your new novel, but do you think this woman’s story was rooted somewhere in the back of your mind long before the dream ever occurred? Simply put, does our imagination feed our dreams?

Hala Alyan: The dream was the radicle of my new novel and I think this woman’s story was rooted somewhere in the back of my mind. There is a reciprocity between dreams and imagination that is beyond anything we can understand and I think there is a way in which I must have gathered, like a lint roller, little bits and pieces for this novel: interest in acting, interest in creative arts, wondering what it’s like to pursue something artistic and have it work or not have it work. My own grandmother is Syrian and I wondered what she would’ve been like if she were a bit more forceful or assertive, what her hopes and dreams might have been beyond a domestic role. It’s very much a consequence of the times but if she had had more opportunities, would that still have been the role she’d chosen? There was definitely a crumb trail in my mind of this woman being built and fashioned and refashioned for years because I dreamt it so coherently, it arrived so whole that it must have been percolating in the back of my mind for a while.

Basmah Sakrani: Beirut is a focal point of The Arsonists’ City and in a sense, the novel captures the beating heart of the city. Was the setting of this novel a given for you or did it come later for you, like roots emerging from the dream-radicle?

Hala Alyan: I often have place and setting first. Even with my newest novel that I’m working on, I knew that I wanted it to be somewhere in the American south, in Savannah, with the Spanish moss and the sort of haunted kind of architecture and setting. The story then balloons out for me, like ink and water, it spreads its tentacles out from place. In my writing, the settings really are another character, another family member. In The Arsonists’ City, Beirut is so integral to the plot of the story and the character development of the story that this family would not have the same things happen to them or develop in the same way if it took place in London or something.

Basmah Sakrani: How do you think your relationship with language first came about?

Hala Alyan: I love the Chinua Achebe quote in that we intend to do unspoken things in this language. I grew up, the first four years of my life, in Kuwait: speaking in Arabic, dreaming in Arabic, thinking in Arabic. Then we moved to the States, where I remember learning English. If I’d always been in the States, maybe learning English wouldn’t be such a strong memory for me because it would’ve just been this natural, gradual thing. But I remember, I actually remember getting cherry and strawberry wrong in something that I’d ordered and being super upset because I wanted cherries. I remember going to the doctor with my mom and explaining my symptoms to my mom so she could explain them to the doctor on my behalf. I remember the first time I was able to read STOP on a sign. I remember learning the spoken language and I think the fact that I had the foundation in another language, it always felt like I had to trade one in for the other. The better I got at English, the worse my Arabic got. When I am in the Middle East for longer chunks of time speaking more Arabic, I forget words in English. It has always felt like there is a tension between the two and tending to one means neglecting the other. French has actually been a reprieve (I have intermediate proficiency in it), and it’s been neutral ground since it is a language I don’t associate with any particular history or past (despite it actually being a colonial presence in Beirut).

Basmah Sakrani: One of the best things about The Arsonists’ City is its construction in three parts, and how, within each, there’s a buildup of these quiet thoughtful moments that greatly define a character’s progression. Do you believe your training in clinical psychology helped shape how you approach these moments?

Hala Alyan: I think clinical psychology and also meditation, like mindfulness training, have really helped me realize and come to terms with the fact that, frankly, most of what we consider to be big moments in our life are actually just the buildup of really quiet, really subtle moments. Training with attention, both through being a therapist and through meditation practice, I’ve come to notice the things that truly change us. Most people are not walking around having big aha epiphany moments, we’re having quiet little moments: shifts of light during the day, glancing at our partner, playing with our pet, listening to our mother’s voice. These little moments add up and change us and so I like to reflect that in my fiction.

Basmah Sakrani: Both your novels, Salt Houses and The Arsonists City, feature multigenerational families. Is this informed, in any way, by your lived experience and the familial inheritances you hold?

Hala Alyan: It is no secret I borrow heavily from my family, not personalities, but structural elements like how we immigrated, the places we’ve lived in, the ways different places filter down and impact people’s development, and the things they hold true and dear to them. I have had the privilege and the luck of growing up closely with grandparents for many years, living with younger cousins as though they were my siblings, and loving my aunt as though she was my mother. This has granted me a window of insight into the significance of intergenerational impacts and how we really are a tribe. This idea of it takes a tribe, a community, a village – I had the luxury of growing up in that and I think that’s why I’m drawn to these stories so much.

Basmah Sakrani: Finally, what do you think is the legacy you’re creating with your words? If they are the radicle, what do you hope will sprawl and stem from them?

Hala Alyan: That’s a beautiful question. I think the legacy I am creating is one of telling complicated, rich, at times contradicting truths. I hope it is a legacy of creating books that contain within them dialectical truths and stories that capture the complexity of what it is to be human, what it is to feel vulnerable, and alone, and joyful, and grateful, and connected, and all these things sometimes all at once. To leave a legacy of writing stories where I show how place, and being dislocated from place, can affect that. On a purely self-indulgent level, I really hope that someday something I write becomes a film. One of the unexpected thrills of writing is meeting some incredible people: booksellers, writers, librarians, interviewers, podcasters, reviewers, journalists. I have met so many amazing people and have had the privilege of such cool conversations and I really hope that I continue to get connected to people in this way and have life expand out further and further and that my writing can be a thing that helps open those doors to meet other people and connect with their stories and vice versa.

Read “gemini” HERE.