This evening I had a conversation with the editor—I will call her Jan—of a small but reasonably prestigious literary journal on the West Coast. At the time of this writing, I’m just a few months past my fiftieth birthday. A little Googling leads me to believe that Jan is in her mid-thirties and would be considered an up-and-coming talent, with one full collection of poetry from an established press and several chapbooks to her name. She is tenure-system faculty at a small liberal arts college where she teaches creative writing and literature.

I had sent Jan’s journal five poems, and they agreed to take one of them—a short piece entitled “Mistaken Identity.” The twist in this piece is that the speaker of the poem is mistaken about his own identity. This fact is revealed about two-thirds of the way through the poem:

And then an accidental glance in a mirror

I happened to pass in the hotel lobby

revealed an entity markedly different from

what I had for my whole life referred to as

me.

The reason for being in the hotel is not revealed, a forbearance that I hoped would generate felicitous ambiguity. Is the speaker having an affair? Going to see an old friend from whom he has become estranged? Attending a funeral of a close relative? Hotels signal trips, and trips signal turning points.

The journal apparently liked the poem (truthfully, it was the weakest in the bunch), and Jan had called me to let me know it had been accepted for publication. In these days of automated online transactions, I was touched by this personal note. I had long thought that literary journals were making decisions via a computer algorithm.

After congratulating me on the acceptance and letting me know that the poem would be published in late fall, Jan inquired about what appeared to be the final line of the poem:

[Insert pretty knotte here.]

“Is this part of the poem?” Jan asked. “Some kind of aside? A stage direction of sorts?”

I explained that the line in question was actually a note to myself. I had considered adding a printer’s ornament (technically, a dingbat) of my own design to punctuate the end of this poem and had intended to delete this note before sending the poem out to journals.

“Ah,” Jan said. “I suspected something like that. I have to say that I’m just a little disappointed. I had wondered if this was some sort of whimsical experimentation with form, a cryptic endnote of sorts.”

The ornamental mark had come about by accident. After writing the first draft of “Mistaken Identity,” I found myself in line at the Secretary of State’s office, waiting to renew my driver’s license. To pass the time, I opened a cheap drawing app installed on my phone and began to doodle with my finger. One of the features of this app was that it took my shaky, irregular lines and smoothed them out using some kind of advanced algorithm. I always felt that there was an implied question mark after these transformations, as if the app were saying to me, Is this what you meant to draw?

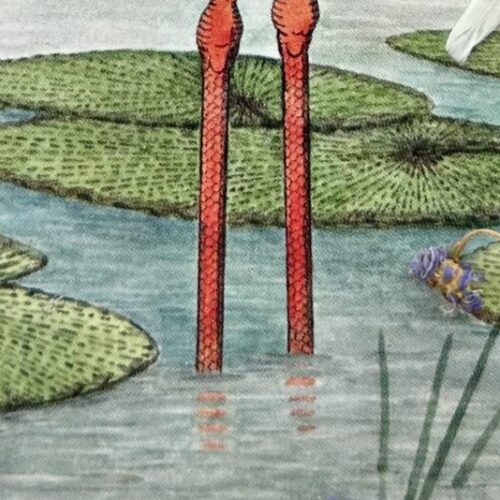

One of these designs immediately put me in mind of “Mistaken Identity.” I had drawn a kind of spiral that curled out into a second spiral. But whereas the first spiral wound tighter and tighter until it formed a dense black dot, the second one closed only so far, leaving a circle of white space at the center. This full/empty pattern evoked a kind of yin-yang balance. The similar but slightly different shapes reminded me of the subtle mismatch the speaker of “Mistaken Identity” feels when confronted with his reflection in the hotel mirror. But the spirals also seemed to hint at two fingerprints that were nearly (but not completely) identical, calling to mind various forensic processes for determining identity — processes that sometimes go awry. We could all name dozens of films, TV shows, and novels that incorporate fingerprints into their plots, many of which involve some form of mistaken identity.

As it happens, I am a bit of a nerd when it comes to bookmaking, and I even teach a class on the history of the book at the university where I work. I could talk for hours about movable type and the letterpress, about the Coptic stitch and the French fold. And I had just read an essay that documented how the sixteenth-century writer Sir John Herrington had been unusually specific in his instructions for printing his translation of the Italian epic, “Orlando Furioso.” Herrington specified the inclusion of a “pretty knotte”—i.e., printer’s ornament—on the title page. So when I returned home from the Secretary of State, I added the half-joking note to the end of my poem: [insert pretty knotte here]. And then I forgot to remove this note before submitting the poem to Jan’s journal.

On the phone with Jan, it suddenly occurred to me that it might be possible to include the mark after all. Perhaps it would add an enticing layer of meaning to the poem. I asked Jan about this possibility. “The image is already digitized,” I said. “I can email it to your designer.”

And that’s where the trouble started.

Jan paused and then answered in a tone that indicated she was mildly annoyed by my proposal. “Well, a printer’s ornament isn’t really part of the poem. It’s something that some designers would add in certain instances. And we’ve never used them here. As I’m sure you know, we adhere to the kind of minimalist aesthetic that was typical of literary journals in the early decades of the twentieth century. For better or worse. In any case, the decision to use a ‘pretty knotte,’ would be the domain of the designer, not the author.”

Now, I should have let the matter drop. To be honest, it had been a while since I’d had a poem accepted for publication, and I was eager to appear in this particular venue. But Jan had inadvertently stumbled on a subject that I happen to know a little bit about. I thought that I detected more than a trace of the schoolmarm in Jan’s tone as if she found it a little tedious to educate me about this elementary aspect of poetics.

“Well,” I said, “you’re quite mistaken there. Authors have collaborated with printers from the beginning.” I summarized the Herrington case for her, hoping she would find the anecdote amusing. Mentally flipping through the syllabus for my class, I added several other instructive examples. William Blake supplied his own illustrations for Songs of Innocence and Experience. More than that, he actually printed the books himself, etching his own copper plates by hand. Walt Whitman, a trained printer and bookmaker, was actively involved in letterpressing the various editions of Leaves of Grass. He specified typefaces and binding techniques, and even designed the stamp used to gold-foil the cover—a highly stylized rendering of the title in which the letters organically merge with leaves and roots.

Jan, for her part, was not about to be corrected by the likes of me. “I think you’re confused about what a poem is,” she said. “A poem is a text. Poets string letters together to form words and words to form sentences. They don’t use pictures or icons or ornaments.”

“What about the ampersand?”

“What about it?”

“It’s neither a letter nor a word. Are you saying I would not be allowed to use an ampersand?” I tried to keep my tone lighthearted, aiming for a kind of mock obsessiveness — witty cocktail chatter.

“The ampersand is a standard mark. It’s not an ornament.”

“It’s certainly closer to an ornament than any of the twenty-six letters. And in terms of its visual composition, the ampersand is often very ornate indeed.”

“You’re welcome to use an ampersand.”

“No, you’re missing the point. The point is that it is impossible to draw neat lines between the poet’s job and the designer’s job. Look at E. E. Cummings,” I said. “Did he use pretty knottes?”

“Not that I know of. But look at the way his poems demand a particular spatial arrangement. Look at ‘r-p-o-p-h-e-s-s-a-g-r’!” I implored, stumbling over the pronunciation, just as Cummings intended.

“Now you’re comparing yourself to E. E. Cummings?”

“Listen, I’m happy to have my poem appear without the pretty knotte. I just wanted to make the point that, throughout history, various poets have played an active role in shaping the visual presentation of their poems. Visual details are often employed to modulate meanings—not just to decorate.”

“Let me ask you a question,” she said. “Let’s say that you end up publishing Mistaken Identity’ in a book. And let’s say that, when you do, a few libraries and bookstores invite you to give a reading. And let’s say you read that poem—which I quite like, by the way. You stand up there in front of the dozen or so people who still turn out for such events, you clear your throat, and you read ‘Mistaken Identity’ in a pellucid, unadorned voice. What do you do when you get to the ‘pretty knotte’?”

I confess that I loved hearing her say “pretty knotte.” It seemed to me she was already conceding my point by using Herrington’s term. And yet . . . in her use of this term, she might have been mocking me. I could discern a faint note of scorn as she placed the phrase in air quotes. I even felt that I could somehow “hear” the redundant t and the silent e, as if she were inflecting a kind of feigned pomposity — the way one might poke fun at an establishment that used archaic spelling to claim for itself an old-timey sensibility (“Ye Olde Butcher Shoppe”).

I was about to answer her question, but she started up again: “You won’t be able to read it. There is no way to translate the printer’s ornament into an utterance. There is no way to perform it. And before you say anything else, I am well aware of the visual tradition in poetry. I know Herbert’s ‘Easter Wings’ and Carroll’s precious mouse tail. There are many journals devoted to extending that tradition. But that’s not the kind of thing we’re interested in here. We can publish the poem. We cannot publish the pretty knotte.”

Well, something in me snapped with that last enunciation of “pretty knotte,” and I told Jan that she had a narrow and unsophisticated understanding of poetry, and that I would try my work on a journal whose editorial practices were informed by a deeper sense of literary history. I wished her good day and then hung up. And, of course, instantly regretted it. The pretty knotte I had drawn was not essential or even very convincing as a printer’s ornament. But there comes a time when you need to fully commit to your aesthetic values.

What is a poem? For Jan, the proof of a poem lies in its ability to be read out loud. But many of us take satisfaction in the unutterable aspects of writing. Who doesn’t love the dagger (†), the lozenge (◊), the fleuron (❧)? Who doesn’t appreciate the graceful curves of braces ({ }) or the rectilinear power of brackets ([ ])? Bracket, not incidentally, is etymologically linked to the Spanish word (bragueta) for codpiece. Brackets are there to protect our most vulnerable words, the thoughts that are most susceptible to attack. From now on, I plan to enclose every line of every poem I write in brackets, little walls to deflect the slings and arrows of unforgiving journal editors.

I want you to know, Jan, that from now on my poems will not contain any letters at all. I can’t use a single pretty knotte? Guess what? As of this moment, I am officially starting a new series of poems, tentatively entitled Knotte Poems, that consist of nothing but pretty knottes. Look for me in Agni and Ploughshares. You’ll recognize my work by its use of algorithmically-perfected lines that sweep elegantly from margin to margin, gathering at just the right moments into Gordian complexities: thick tangles that far surpass the expressive force of your precious “letters” and “words” and “sentences.”

Thank you, Jan, for goading me into inventing an entirely new approach to poetry — one that takes us beyond language, beyond meaning, into a trance that follows the flatness of the page in a flow of semantic purity heretofore uncontemplated.

Thank you, Jan, for helping me appreciate the power of wordlessness.