Music can affect what words cannot. Jennifer Rosner’s debut novel, The Yellow Bird Sings (Flatiron Books, 2020), is about the remarkable bond between a mother and daughter forged during the Holocaust. It is a National Jewish Book Award finalist in two categories (Debut and Book Group), a Massachusetts Book Awards Honor Book, a Goodreads Best Historical Fiction Book, and Massachusetts Book Awards has designated it a “Must-Read Book.” In The Yellow Bird Sings, the author borrows inspiration from the Brahms Scherzo—both structurally and metaphorically.

In 1941, Nazi-occupied Poland is a hellscape whose horrors include genocide, the routine raping of women, the severing of families, and the permanent dislocation of millions. Here, where words are weapons and one’s birth name can be lethal, music proves the most durable path to memory, salvation, and connection.

Brahms’ Scherzo in E is a complex, emotionally volatile piece, just as Rosner’s novel engages equally complex questions a parent must answer as she attempts to raise her daughter within the confines of an impossible situation. The Scherzo is the final movement of the “F-A-E Sonata,” written with Franz Schumann and Albert Dietrich as a gift to the famous violinist Joseph Joachim, whose personal motto Frei aber einsam (“Free but lonely”) gives the work its structure. Like the Scherzo–a duet between violin and piano–the novel is composed of two voices, with chapters alternating between the perspectives of mother and daughter.

Roza and her husband Natan were classical musicians, raising their five-year-old violinist Shira in a home imbued with the sounds of their stringed instruments. But when Natan, forced to labor for the Nazis, was made to dig his own grave and soldiers came to drag away Roza’s parents, throwing them into cattle cars while Roza and Shira watched from a closet, mother and child fled to the hay-strewn loft in a nearby barn where Roza must keep Shira quiet and still or risk their deaths. But how to silence a child under any circumstances or explain that being Jewish differentiates Shira from the farmer’s sons who are shouting, playing, and walking in daylight?

At no point in her narrative does Rosner settle for absolutes. The holding together of life—even holding together oppositional ideas—is a central theme of the novel, and this too reflects the Brahms Scherzo, which alternates between vigorous martial passages and lilting pastoral ones. The farmer Henryk and his wife Krystina save the lives of Roza and Shira, but their safe harbor comes at a price. Every night, Shira must lie facing the wall while—inches away—her mother surrenders to Henryk’s visitations. When Roza becomes pregnant, she forces a miscarriage, then realizes the bloody remnants will surely be discovered by Krystyna. The frozen ground prevents her from digging a hole to bury the remains. In desperation, she kills a rabbit and tears it with a trowel “the way a wolf might.” She leaves the valuable meat on top of her bloody discharge—this is, after all, war-ravaged Poland. Seeing how entirely he has trapped Roza forces Henryk to recognize her humanity. In doing so, he is somewhat humanized. He becomes gentle, caressing her cheek, helping Roza nurse Shira back to health when the child is ill. While reading these scenes, I wept in frustration at the eternal powerlessness of women.

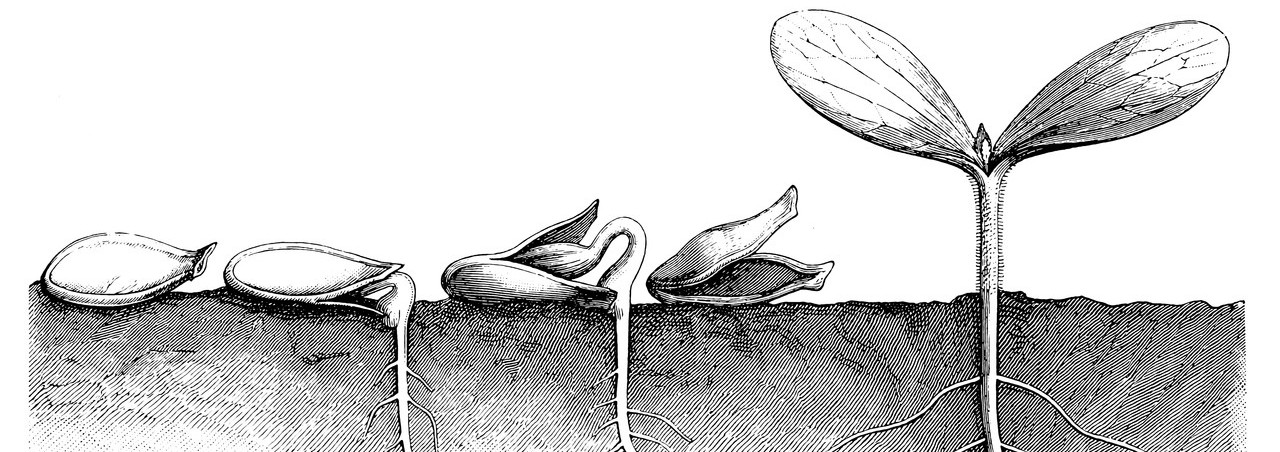

Out of the trauma of losing her father and grandparents, Shira has conjured an imaginary yellow bird, who mostly dwells within her cupped hands. To keep her daughter silently occupied, Roza composes stories about this brave little bird, who sings so that Shira may keep her own music “inside.” But Shira is a prodigy whose small fingers, remembering their little violin, constantly tap out the rhythms she hears. She yearns to hum these melodies but agrees to let the bird warble them instead. She begs her mother to write down the notes of the Brahms Scherzo, a piece Shira has heard her father play. The Scherzo begins with great crescendos of minor, martial, and repetitive notes, the sound of danger and clomping boots, and people rushing. Then, it moves into a lyrical passage, pastoral and emotive, hopeful, with major chords and an upward tilt. The two moods of the piece converse, grow, and evolve, landing in a place that is quietly triumphant and also resigned, or as Roza notes, “The ending comes as a gift, a surprise placed into cupped hands, expressing affection so powerful as to banish all its loneliness.”

Joachim’s motto “free but lonely” serves well as Roza’s lodestar. While Krystyna sometimes threatens to evict the refugees, her genuine pity and kindness override her fear. A mother of three sons, she is drawn to Shira, taking the girl on short walks around the barnyard, feeding her eggs and bread, and bringing her books. Eventually, she proposes to secret Shira to a convent, forcing Roza to choose: banish loneliness and keep her child close—greatly increasing the odds that both will be killed—or let her go and gamble on freedom and potential survival. Though Shira loses her mother, music indeed becomes her ticket to freedom. After the German commandant overhears her playing in the convent, the nuns find a talented and loving teacher to give her free violin lessons. Locating her during the post-war months, a Rabbi re-connects Shira with her heritage after drawing forth her history by humming a song she recalls from her childhood.

“Life,” Rosner’s characters come to understand, is “the holding together of small broken pieces.” Shira’s very name is in shards—to protect her identity, she is renamed by the nuns and later by her adoptive parents—but her connection to the Scherzo remains the daisy chain Roza promised her, linking girl to mother, even when both of them lose the handle of the other’s name. Ultimately, Shira’s dedication to music, how she tunnels all of her emotions—her secrets, her stories, her past—into her violin, provides the bridge by which she may finally reunite with her mother.

Worldwide, at this moment, people continue to face agonizing decisions about leaving homelands in the face of rising violence, displacement, genocide, and autocracy. In times such as these, adults and their children endure by engaging in the same dedicated, meditative, focused pursuits Shira exhibits in “practicing” the violin without a physical instrument, or Roza’s illustrating for her child the difference between quarter notes and eighth notes by breaking strands of hay into various lengths. We need such narratives, confronted as we are with plagues, wars, and looming extinction. We want books that celebrate the ability to remember an 18-note phrase or methodically translate an ancient text, to remember the power of the arts to sustain human life under the worst of circumstances.

Available now at Bookshop.

Nerissa Nields

Nerissa Nields is a writer and musician living in Northampton MA with her husband, children, and Australian Labradoodle. She is the author of Plastic Angel, How to Be an Adult, All Together Singing in the Kitchen: Creative Ways to Make and Listen to Music as a Family. Her first short story is forthcoming in J Journal, and she is currently working on a trio of novels about a family rock band, not unlike her own. She holds a BA from Yale University and an MFA from Vermont College of Fine Arts.