Gretchen Legler is a teacher, a writer, a sketcher, and an avid gardener who earned a Master’s of Divinity from Harvard Divinity School. When I asked about her history as a writer, she said, “I have always been one. It was a gift.” She wrote and illustrated stories as a child and later wrote for student newspapers and literary magazines. Her dream was to be a foreign correspondent, but she ended up enrolling in the graduate writing program at the University of Minnesota, where she tried her hand at fiction but, in the end, gravitated to nonfiction. Legler is a seeker at heart. She lands in remote places and, in a voice as natural as rain, writes award-winning books about her experiences, On the Ice about living in Antarctica, All the Powerful Invisible Things about being a woman in the outdoors, and most recently, Woodsqueer, Crafting a Sustainable Rural Life published by Trinity University Press, about survival in rural Maine. Her sacred relationship with nature is palpable in her prose, and at the same time, she speaks openly and honestly about the fallibility of being human. It was a joy to ask her questions about her life and craft. I can’t wait to read more of her work.

~Megan Vered, Radicle Interviewer

Megan Vered: This book is a lovely read about finding faith, awe, and resolve in the arms of nature. What made you decide to write a series of essays rather than a memoir? Did you envision the structure before you wrote the book, or did it emerge as you wrote?

Gretchen Legler: I have always considered myself an essayist first. I LOVE the essay form. Just like Woodsqueer, my first and second books were both collections of essays that were later arranged to tell a story of a time and place. Most of the essays that make up the “chapters” of the books I’ve published appeared first as essays in magazines and literary journals, then later came to be “chapters” in book-length nonfiction narratives. When I worked with the editors at Seal, Milkweed, and then Trinity University Press, they were reading for “narrative arc” and pointed out parts of the larger story that might need to be filled in, so I did add some narrative “glue” to make the essays cohere.

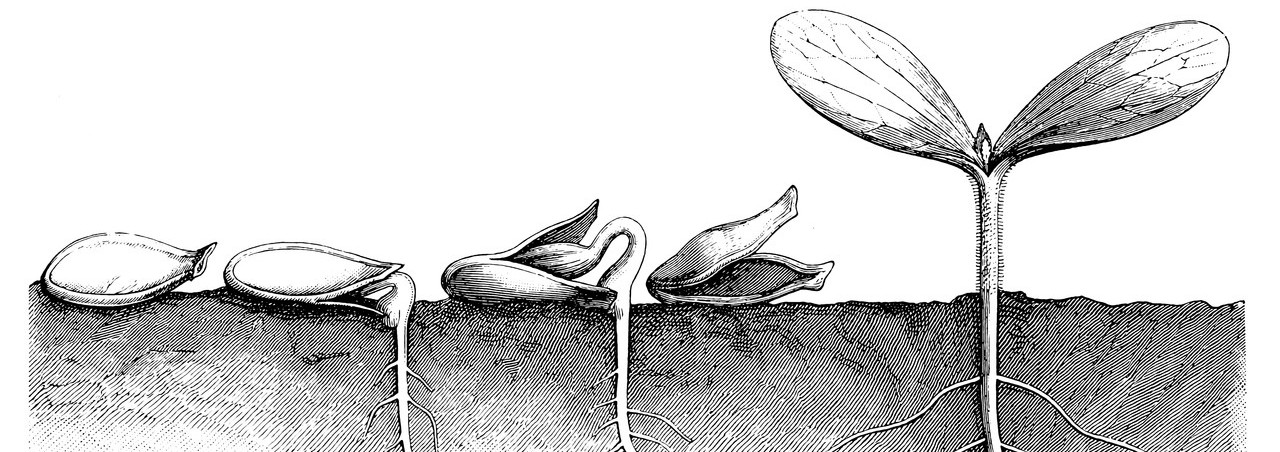

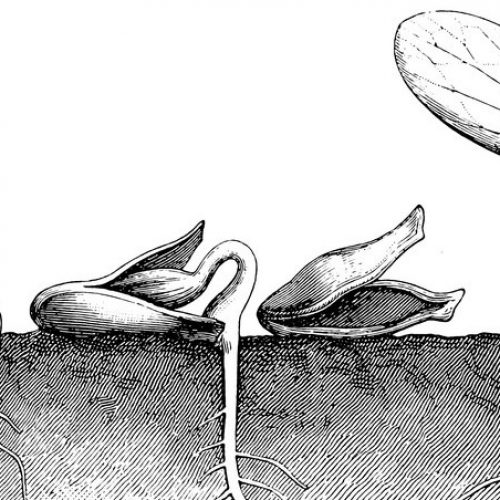

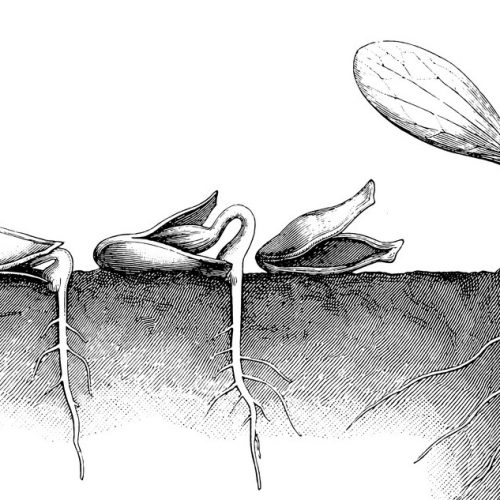

Megan Vered: Your sketches add a delightful and educational visual dimension to the reading experience. What comes first for you, writing or drawing?

Gretchen Legler: The sketches were a pure accident, and one of the really great things about working with editors who are excited about your work and can help you bring it to life. In the essay about heating with wood, I had, just for fun, sketched some different styles of woodpiles. When one of the wonderful editors at Trinity University Press, Margy Avery, read the manuscript, she asked for more sketches. I have never considered myself any kind of skilled artist, but I accepted the challenge. One of the things I love about the inclusion of the sketches is that it puts Woodsqueer in the company of other classic pieces of Maine environmental writing, like Henry Beston’s Northern Farm, Bob Kimber’s A Canoeist’s Sketchbook, or Bernd Heinrich’s The Trees in My Forest. As a writer, I really value the practice of sketching because it brings me into intimacy with what I am looking at. I feel like I know a landscape or a creature more deeply after I’ve spent some time really trying to give voice to its shapes and shadows under my hand.

Megan Vered: Can you describe the struggles you faced while writing the book? How did you deal with them?

Gretchen Legler: The struggles I faced were what all writers of personal nonfiction face—what to put in, what to leave out, and how much to reveal about oneself and others. Judith Barrington, who wrote Writing the Memoir: From Truth to Art, advises not to censor yourself when your writing is still relatively private. At first, say what needs to be said. Later, when you are about to send your work to a journal, magazine, or publisher, decide, based on your own values, what you want to leave in. For example, I had a line in the book quoting a cousin saying something unflattering about my grandmother. I took that out in the end. I also struggled with the pain of some of the things I wrote about—the upheaval in my relationship with my partner because of the affair. It was painful when it was happening, and painful to revisit in editing the book for publication. I fall back on the advice of writing mentors like Robert Frost: “No tears for the writer, no tears for the reader…” If we don’t experience our own pain when writing about painful subjects and events, then how do we expect to convey that sense of intensity and vulnerability to our readers?

Megan Vered: Your book is about having your hands in the earth, about the claiming of land, and at the same time about what you unearth inside yourself. I’m interested in hearing more about the dynamics of the interrelationship between the claiming of land and the claiming of self.

Gretchen Legler: I love the way you asked this question. It’s complicated. I have always been interested in materiality–the “solid earth, the actual world” (as Henry David Thoreau put it). My father was a biologist who studied turtles and snakes. My mother loved to collect weeds and seed pods. But despite this grounding in the material world, somewhere in my life (and my guess is in the lives of many of us), I lost the connection between the material of my body and the material of the earth. Perhaps in my family, this was rooted in the denial of my girl body or child body as a means of protecting myself from harm—you kind of become “not a body.” And once you get on that train, you keep going on this flight from the real. Our overwork culture denies the needs of the body, consumer culture generates endlessly unfillable desires, and academia theorizes the body to smithereens. For me, healing has come from connection with dirt, animals, trees, rocks, and water. You ask about “claiming land.” I feel a little uneasy with the word “claim” because of the implication of dominating or owning. I would say I claimed a place for myself in the land.

Megan Vered: Yes, claiming a place for yourself in the land. This relates to my next question about sustainability, a big concept in your book. I’d like to hear more about what the term sustainable means to you relative to your relationship with yourself, your love life, your spiritual life, and the environment.

Gretchen Legler: What I mean by sustainable is a life that you can keep on living, individually, emotionally, personally, as well as culturally, politically, nationally, and globally. A balanced life that doesn’t use up available resources. A life that isn’t just about what you want right now. Americans have a reputation for moving fast and hard. We use things up and throw them away; we use up our bodies, we use other people, we use the land. Sustainability, if you bring it down to a very intimate level, means trying to live in a way that honors and respects other people, animals, land, and water. There are all kinds of ways to live more sustainably. My partner and I collect gray water in a pot at the kitchen sink –water that would normally go down the drain into the town sewer system. We use it to water our garden. This is a simple example of sustainability. We are taking care of a precious resource and using it wisely. On a personal level, I am influenced by the cultural pressure to overwork which only makes me sad, exhausted, and not very generous. In the book, I write about the cultural pressure (maybe I should call it permission) to indulge my sexual desires, whatever the cost. But that is not sustainable either—at least it wasn’t for me.

Megan Vered: You pursue two parallel and, you might say, opposing threads in this collection—on the one hand, your circumspect relationship with nature, and on the other, the impulsivity of being human. You handily master the art of killing a chicken, skinning a beaver, and plotting a vegetable garden, but struggle to sustain love in your romantic relationship and, most importantly, within yourself. Did you think about these threads while you were writing?

Gretchen Legler: Humans are complicated. We can be wary and impulsive. We can be incredibly reflective and skilled and also inept and un-self-aware. We often work against each other, nature, and ourselves; it is human nature to be imperfect—to struggle against the flow, but also our nature to search for ways to be in harmony with what is. I’m not sure I was aware of these threads as themes when I was writing but exploring the fraught relationship of the self to the higher self, and the self to the world, has always been my deepest subject as a writer. As a nonfiction narrator, you have the ability not only to see yourself and others in your work as characters, but the ability to craft yourself as an “unreliable” narrator, just like you might see in a novel or short story. I enjoy playing with the idea of making myself an untrustworthy narrator of my own life. The reader will see me doing one thing—butchering a flock of chickens—and also hear me saying that killing other creatures is disturbing and awful. The reader will see how much I yearn for a grounded and loving long-term relationship with my partner, and then see me endanger that by having an affair. This is what it means (for me) to be human—to acquiesce to my fallibility and vulnerability.

Megan Vered: The cycle of life in both nature and animals is a big theme in your book. We are brought face-face with death multiple times. Your mother. Your father. Your chickens. Big Red the rooster. Nima the goat. Can you say more about the rituals surrounding death that brought you comfort?

Gretchen Legler: I took three years off from teaching at the University of Maine Farmington to go to Divinity School. I learned a lot about ritual and came to understand that it gives us an opportunity to stop and focus our attention on what we are doing in that moment, or in our lives. It opens a crack for the sacred to enter. It also creates “soul community.” The finality of death is so frightening. Life goes out. The body expires. People and animals live on in other ways, of course, but the body as we knew it is gone. Being with animals and experiencing their deaths, especially having a hand in their deaths (in the case of butchering chickens or hunting deer), gave me an even more profound respect for the frightening power of death. What do you DO in the face of that? You create ritual. One of the most healing rituals is simply gratitude. It became increasingly important for me to say a version of “grace” before eating anything that had come out of our garden or any animals that we had raised or hunted and then killed to eat.

Megan Vered: What prompted you to attend Divinity School? How did that influence your view of your life, you as a writer, and the writing of this particular book?

Gretchen Legler: I have always, since I was a child, had a deep interest in “religion.” I grew up in Salt Lake City, Utah in what I call an “anti-spiritual” family. My father’s parents were Unitarians and my mother’s were Lutheran, but neither of them had a spiritual life or religious community. My father thought churchgoers were idiots—you know—“opiate of the masses” and all that. Maybe part of my interest in religion came from it being forbidden. There are many answers to the question of what drew me to Divinity School, and most of them, I think, boil down to insatiable curiosity and desire to learn. I am fascinated by world religions. Where did these systems of belief come from? All these different origin stories? Did we all hatch out of a cosmic egg, or are we the children of Spiderwoman, or are we the children of Adam and Eve? What happens after we die? After three years in Divinity School, I still would not call myself a “religious” person, but I am a person who values spiritual community and ritual. In Woodsqueer I write about the ritual of “coming to nature’s table,” eating foods the earth offers up for free at a communal table with members of my church, where we share the bread of life and the cup of blessings. One of the most important elements in my own healing is the recognition that I am not alone (we are all human, all broken, all flawed, and all capable of great joy, generosity, and compassion), and I deserve to be “at the table” – to be loved and valued just as I am. I don’t have to be perfect. These are healing messages that are part of the best spiritual and psychological teachings.

Megan Vered: So much healing took place in the context of your relationship with Ruth. You got legally married before going to Bhutan where you were a Fulbright Teaching Fellow. I would love to hear more about how that experience shaped you, both personally and professionally.

Gretchen Legler: The Kingdom of Bhutan would not allow Ruth to come live with me unless we were a married couple. Initially, I don’t think they understood that we were lesbians. Later, I heard that someone in the Bhutan foreign office felt proud that they had, for the first time, issued visas to a lesbian couple. We lived and traveled in Bhutan for about seven months. We taught writing and songwriting workshops in the university system. We flew from one end of the country to the other on one of Bhutan’s first domestic flights. We were present for several other Bhutanese firsts—first parliamentary election, first issuing of bank credit cards and bank loans. Our experience gave us a way to measure how “rich” our lives are in the U.S.—in terms of cultural and public resources, consumer goods, technology, transportation, public services, educational resources, personal freedoms, job opportunities. Bhutan then was (and still is) considered a very “poor” country in terms of gross domestic product, but it was trying hard to figure out a new way to measure its success as a country and a culture. The 4th King came up with the concept of GNH—Gross National Happiness, instead of Gross National Product—an alternative development model. Let’s not measure our success on goods and services produced, but on how content our people are. This concept reverberated in the media and people started saying, “Bhutan is the Happiest Country in the World.” Turns out that is not true. But it caused me to wonder if Bhutanese people were happier than we tend to be, statistically speaking, in the U.S., despite their having fewer resources. What I saw was that most Bhutanese lived in much closer relationship with the “unseen” than we do. There was a deep sense of the landscape as inspirited and of the sentience of places and animals. Bhutanese forests are full of shrines, prayer wheels, and monasteries. Spiritual life is very present. This made me ask if there might be a direct relationship between “development” and the severing of one’s spiritual relationship with place. Is it possible to have a modern industrial society with some of its benefits (roads, electricity, clean water, a warm and sturdy house, some job-creating industry, communal food production) AND still maintain a respectful, intimate relationship to land and non-human others?

Megan Vered: On the subject of spirituality, I found the spiritual crescendo in the final chapters of the book very moving. In one of my craft books, written in 1951, the author compares the flow of good conversation in an informal essay to following a stream to a larger expanse of water where the eye takes on a larger vista. How would you compare your book to this metaphor?

Gretchen Legler: That’s such a great image—water following into a larger expanse—a lake, or pond, or the ocean. I guess that sense of vastness and possibility is something that I consciously tried to craft at the end of the book. Once you know what joy is, anything seems possible! From a craft perspective, I have always been fascinated by the “crescendo,” as you call it. I listen for it in music, I look for it in art and film. My sense is that it is kind of like melody these days—regarded as old-fashioned. A writer I admire who does that “crescendo” thing is poet Mary Oliver. Her poem “The Honey Tree,” is a good example. I sometimes like to end essays on small notes, but small notes that open out, as you suggested, into bigger bodies of thought. But in this book, I really wanted to try to convey something BIG: what it felt like for me to sense that I was in the right place at the right time, that I had exactly what I needed to live a great life, that I mattered to the people who loved me and was beloved by the universe itself—just exactly as I am.

Available on Bookshop.