It was too hot to be out, but no one complained because our good friend Annie was dead and we didn’t know how to talk about it. We sipped tall cans of sweet tea and ate unshelled peanuts, tossing their crepey husks in a vacant clay pot that once held a kumquat tree. There should’ve been a pool in this unfenced yard bordering the steaming golf course, but there wasn’t. In fact, it was the only home in the whole desert subdivision that didn’t have one.

Annie died from a type of cancer the doctors said was slow-growing. They said it’d creep through her bones so slow she’d barely notice. Like a mild flu she’d have forever, one of the doctors had said optimistically. She was 28 when she got the diagnosis and two months later she was dead. Dead as a Kmart parking lot on Christmas Eve. As in, there were lingerings. Those of us who knew her the least felt like she wasn’t really gone. Like we’d left for college and found out via voicemail the family cat got put down. Those of us who knew Annie well felt her absence like a gnawing hunger—hence the peanuts.

Janice used a takeout napkin to wipe the sweat from her brows. Some of the dark brown powder she used to fill them in went with it. “Is this what it feels like to die on Mars?” she asked no one in particular.

Eli answered, “Mars is cold.” He sat in a sliver of shade peeling his fingernails down to the quick. “Below freezing on average. In the summer, the equator will reach a high of 70, but that’s it.”

“Huh,” Janice said. “I always thought it was a touch shy of boiling.”

“Nope.” Eli bit off a hangnail and spit it into the bushes.

“Well, whatever. I want to have my ashes scattered on Mars and become one with red dust.”

Janice flipped over to even the sun’s score on her skin. Eli pulled his knees to his chest. Sammy laid on the concrete with her naked chest facing the sky, an old issue of Horse Illustrated covering her face.

“Why don’t you stay here and grow yourself into a carrot?” I asked Janice. “Add your tops to the compost pile and become perpetually new?”

Janice raised her lighter eyebrow. “No carrots for me, thanks. Too phallic.”

“I need someone to itch my rib,” Sammy said from underneath a double-page spread of miniature horses for sale. “If I move now it’ll defeat the purpose.”

Janice looked to Eli, who held up his chewed fingertips and shrugged. With a sigh, she crawled across the patio and scratched Sammy’s side using just her index finger.

“Happy?” Janice asked when she was finished.

“Obliged,” Sammy said.

With at least an hour to go before sunset, the back of my shirt was soaked, but I didn’t dare move from my spot. These were the ones we’d picked and these were the ones we’d stick with, lest we spook some part of the spell. Besides, being close to the house gave me a panoramic view of hole 13.

A breeze came and flipped a page of the magazine covering Sammy’s face. Instead of miniature horse classifieds, now it was regular horse classifieds. The smaller the horse, the longer she lives—everyone knew that. But depending on how old the issue was, they were likely all dead anyhow. I let that thought sink in as I stroked the barrel of my 20-gauge shotgun. My skin smoldered on.

“Did you hear that?” Janice said, springing upright in her chaise lounge.

Eli grumbled and Sammy sighed.

“It was just the breeze,” I said. “We’ve got time.”

“We are time,” Eli mumbled under his breath.

What nice things can I say about Annie? Annie was long and narrow like a string bean that’d sprouted arms and been infected by a musical improv obsession. She wasn’t attractive by conventional standards, or even unconventional standards, but she had a knack for inventing show tunes on the spot. At her shows, when people in the audience would shout out the requisite suggestion word, she’d always find a way to bring it back to her other main passion, board games. At the suggestion of nursing homes, she belted: Hang on to your bladders, we’re playing Chutes and Ladders. Tater tots: Before we venture to the land of Catan, preheat the oven and oil the pan. Greed: Did you know that in 1903, a bunch of anti-monopolists created Monopoly?

None of us wanted to admit feeling relieved by the thought of never going to another show.

“I know no one wants to acknowledge this,” Janice said, uncrossing and re-crossing her legs, “But how will we know which one?”

“We’ll just know,” I said.

Janice slapped a fruit fly off her knee and frowned irritably.

The sun had begun its descent. Now it was just a matter of time. I pinched open a peanut shell and found nothing inside.

I remember the look in Annie’s eyes when she finally realized she wasn’t going to make it. It was her second week straight in bed and she wasn’t getting better. She had three separate cups of ice chips by her bed in varying stages of melt. Someone brought up the idea of bringing the stage to her, setting it up in a corner of the room complete with cushions and lights and a mic lowered as close to the ground as it would go. In addition to performing for us, she could perform for the rotating cast of nurses and hospice workers who cycled in and out of her room. The person who said this—I can’t remember who—had meant it to be thoughtful, encouraging even. Annie hadn’t taken it that way. She said her body remained but we’d killed her spirit.

We’d killed her. We were going to kill her. She was dead. She wasn’t. Did it really matter anymore which way it was, one way or another?

“I just think it’d be good to have some kind of signal,” Janice said.

“A signal?” said Eli.

“Like, a look. When the moment arrives so we can all agree. Am I the only one who thinks this should be a democratic process and not some wild west, fly-by-the-seat-of-our-pants bullshit?”

Eli rolled his eyes.

Janice caught him and snapped, “Let me guess, democracy is a sham and time isn’t real and all of this is in our heads.”

“It’s not my fault you think linearly,” Eli said.

Janice threw her hands in the air and let them drop to her thighs with a wet slap.

“Come on, you guys,” Sammy groaned beneath a double-page ad for fly spray. “Come on.”

When I first arrived in Los Angeles, Annie was the only person I knew. She drove all the way from our one-horse Texas hometown and so did I—six months after she’d scoped the place out. The plan was for me to crash on the floor of her apartment, a cigarette-stained studio at the airless Kingsley Manor, until I landed a job and a place of my own. When I arrived at her doorstep clammy and near-blind from driving west into the mid-afternoon sun, she said let me buy you a banana shake. Sitting on the roof of her car surrounded by fast-food detritus, I’d asked her how she wanted to die.

She thought about it for a long time. She sucked up her soda and chewed on her straw. “I’d like to be obliterated,” she said finally. “Vaporize me if you can. Make sure there’s nothing left.” She had always been about tidy endings.

And now all I can think, whether I’m awake or asleep, is Annie get your gun, Annie. Annie get your gun. Annie—

“That’s it, that’s definitely it,” Janice said, springing out of her seat.

Sammy lurched upright, her face puffy and slick. “Oh fuck.”

That’s when I heard it, too. From a slant, it sounded as though a herd of fingers was paddling the arm of a leather chair.

“Steady yourselves,” Eli said, voice quivering.

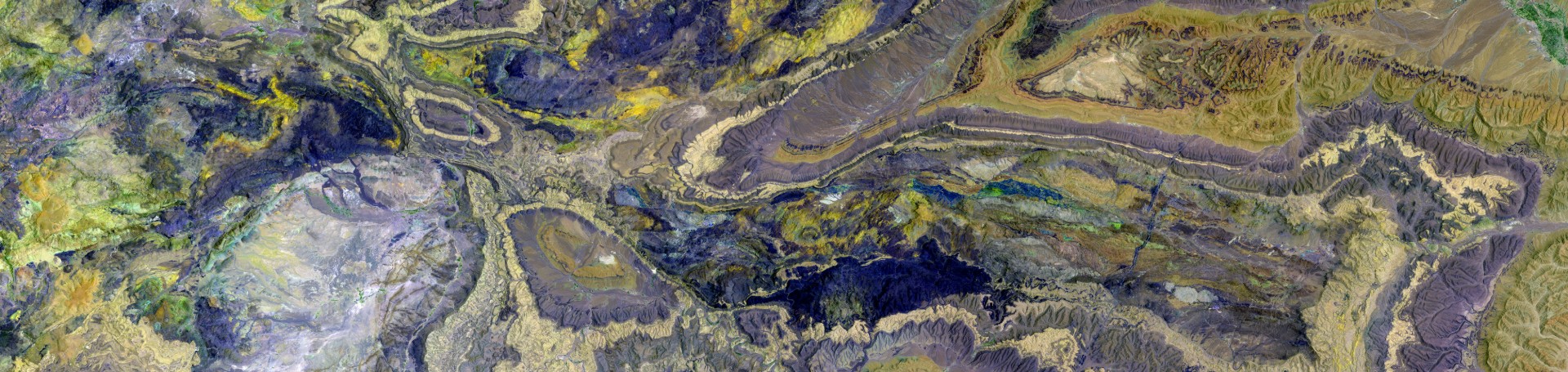

Then the unmistakable thrum. Like a door closing shut, they were on us, a wave of green-gold flecks thundering down the fairway in the fading afternoon light. Together they spanned the width of the golf course, and despite numbering in the millions, throbbed as one body, fluid and loud as a cloud of pennies. We all remained perfectly still as they thundered past. Though no one said a word, we all feared one misstep could direct their needle-like beaks straight into our doughy faces.

Janice sat on her heels transfixed by the storm. Her cherry red nail polish lay splattered on the patio beneath her, a miniature crime scene. Sammy sat upright, her legs straightened out in front of her like a rag doll. Eli wrapped himself into a ball and buried his chin behind his knees. We were poised for the apocalypse, or at least as much as our personalities would allow.

Just as they were about to pass us by, one cut away from the pack and perched on the lip of the pot full of peanut shells. She tilted her head to get a good look at us. From what I could tell she seemed to be sizing us up, squinting like she was, but it was hard to see from such a distance. Then she opened her mouth and let out a blood-curdling screech, something I didn’t know hummingbirds could do.

She flapped her wings slowly enough for us to see the movement involved. Concealed by 80 flaps per second, you’d assume her wings would beat straight up and down, fighting wind and gravity to keep her feathered olive body suspended in mid-air. But slowed down, it was easy to see the wings as the forearms they were. Slowed down, she looked like a debutante waving her arms from atop a Thanksgiving parade float—theatrical even.

The impact obliterated her small body. It was over and she was gone, gone as any living, breathing thing can be. I leaned my shotgun back against the wall and sat in a lime green lawn chair, my quaking limbs making an imprint on the dust.

“I thought we’d at least say some words,” Janice whimpered.

“It’s better this way,” Eli said, suddenly stoic. “Less permeable.”

In lieu of words, we sat among the emerging stars. It could’ve been ten minutes or two hours that we were out there in the growing cold. Eventually our hive mind drew us back inside where food and warmth and twisted dreams awaited us. If we didn’t remember what we’d dreamt the next morning, there was a very good chance we’d never remember it at all.

Kate Ryan

Kate Ryan is a freelance writer. You can find more of her deranged short fiction on Instagram at @theonlyshortshorts.