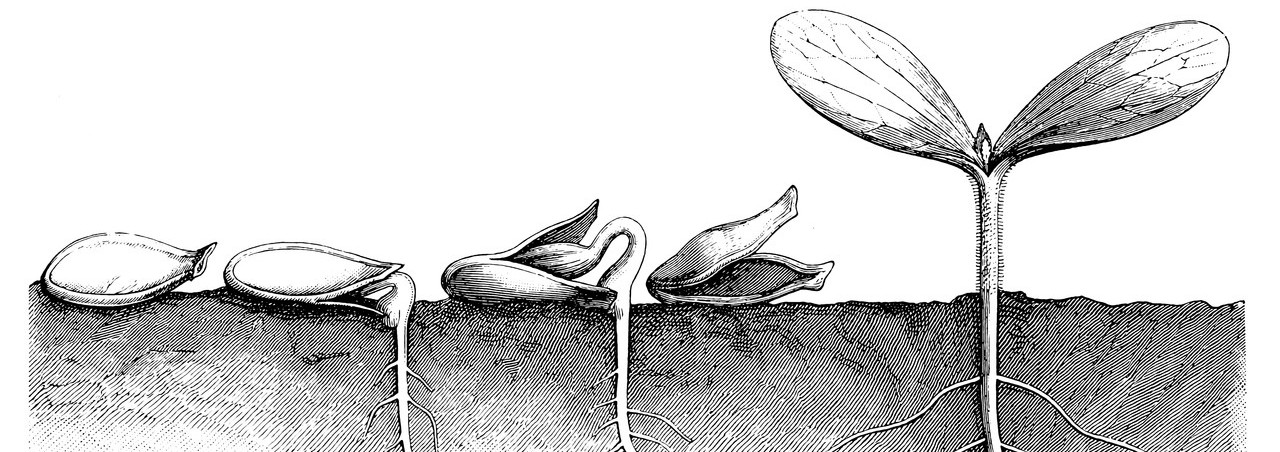

Fred D’Aguiar is a celebrated British-Guyanese poet, prose writer, playwright, and Professor of English at UCLA whose career has spanned 35 years. D’Aguiar’s many accolades include earning a Guyana Prize for Literature and being shortlisted for the T.S. Eliot Prize and the James Tait Black Memorial Prize. As a writer, D’Aguiar intimately engages in what he describes as the writer’s “inevitable contract” to contend with both the present and past. His most recent book, Year of Plagues: a Memoir of 2020, published by HarperCollins in 2021, recounts experiences battling the plagues of cancer and anti-Black racism during the COVID-19 pandemic. His first collection, Mama Dot, both pays homage to his grandmother and is what he calls the radicle, or root, of his career.

~Shanta Lee Gander, Radicle Interviewer

Shanta Lee Gander: From your first book, Mama Dot, to your latest work—including your memoir and Letters to America—what would you say is the radicle of your writing career?

Fred D’Aguiar: I love the idea of radicle; it’s a lovely homonym suggestion and a natural image as well…the idea of the earliest beginning being the one that’s fundamental. For me, it’s such a clear thing. It’s the countryside of Guyana, living with my paternal grandparents, my grandmother in particular. I locate her as the central radical as it were, in tandem with the place. The two together actually—there is something about that. Although history was moving on, and we were in some kind of moment, the location took us out of whatever those large currents were, and made us feel like children, that we were having a good time. I think it was fundamental for me in all kinds of ways.

Shanta Lee Gander: Did you know that at the moment, or did you know in your reflection? I remember when we talked about Mama Dot, and how it was unzipping for you, especially during the grieving process when your grandmother passed.

Fred D’Aguiar: I was 21 or 22 and I was in London. My grandmother was in Guyana, in the same house where we grew up. She died in the house, and so I was thinking about her. I realized the poems I was writing about her took on a life of their own. They were spurred on by her life and rooted in her life and in the place.

People have been interested in the idea of the caregiver, the Black woman, how that is her role in history, and it’s a terrible role. And I can see how, as a concept, it’s not good. It’s not healthy to pigeonhole someone in that way. But for me, it literally began as a series of elegies for my grandmother. I realized from making my grandmother larger than life—treating her as a figure who was guiding me philosophically, keeping me safe, and feeding me—that I was doing something that was slightly mythical, though my grandmother did all of those things I described. I’d become aware of it once I got a handful of poems. When I got to poem number ten, I realized I was doing an exploration—methodically and conceptually—writing beyond the thought and grief of her. I thought that this was my poetry that began with my life as a child with her as a person in that place.

Shanta Lee Gander: In a recent interview, you talked about how “…poetry insists on secular and spiritual in unison. Poetry wants to be body and mind and spirit to show what the three can do they pull their resources in a language held in common.” With the pandemics of racism and COVID, combined with your own health, how do you maintain secular and spiritual unison within the fatigue of the moment?

Fred D’Aguiar: We’re in that moment. We are forced to reflect on it as we must, even though it’s unfolding. This hellish experience isn’t just mine; it’s to do with Blackness, class, racism that’s tied to the system. The heritage of that goes back to a landscape founded on slavery and clearing the land, so I do feel that tension. And the tensions we are in now have this long, long history, and there is a need for wellness that we have to practice even with the burden and the trials of all of that.

I think wellness comes out of first seeing a unity between body, mind, and spirit. In our culture, they’re separated and given a kind of material value. You can buy vitamins, or you can purchase a weekend in a retreat as if these things are completely compartmentalized. They are not, at least not in poetry that is worth it’s salt. That poetry is intended to lean right across all three [body, mind, and spirit].

Just as the body, mind, and spirit are under attack in this contemporary moment and separated and parceled out for brutality, I’m forced to think about them as working in unison. And so, for me, it’s the practice of reading and teaching, which I really enjoy, though some may say, “You enjoy teaching! What’s wrong with you?” I learn so much from the classroom that has to do with wellness and this idea of the routes towards those roots.

I was teaching the book The Life of Olaudah Equiano, penned by himself. I teach it once a year and, each time, I think I know the book back to front. Students will say something that tells me there is more. I love that moment, and this time it had to do with Equiano and his wife, Susannah. He got married in the UK, bought his own freedom, and it doesn’t say much about his wife except to say Susannah brought him comfort when he felt most alone. He found love. Equiano returns to the mission of talking about slavery as a thing that must come to an end, that white Christians needed to stop being slavers. Right at that moment, Equiano revealed something personal about himself and his own wellness, but a bigger question—emancipation—had to be maintained for him. You must keep your eye on the ball, whatever that might be. For Equiano, it was emancipation for everyone, all Black people. It meant that he couldn’t talk about falling in love, but he would let us know that there is still room for love in the middle of what appeared to be overwhelming despair.

In the classroom, we’d spent a whole lesson talking about what it was and how does one procure that, and foster that sense of wellness, even as you’re facing some huge currents that can sweep you away. It reminded me of the historical mission. It is not my term, but the idea of remembering the dismembered. The idea that that history itself is about pulling people apart, forced transportation, the scattering of families. A lot of the historical mission is to put that back together. As a writer—in a poem, a place, through an imaginative act—you bring it back together through an act of narrative, vision, argument, and song.

Shanta Lee Gander: I was thinking about the moment and talk of liberation, though it has become a buzzword. I keep thinking about that concept, especially self-liberation within a culture and land that has been sick for a long time, which is not necessarily unique to America. How do you parse this idea in a way that also actively brings the mind, body, and spirit together in unison?

Fred D’Aguiar: One thing you don’t do is make it an individual quest about you and your ego finding some kind of light. There is a quest, but it’s not towards ego. It’s towards wellness, a connection with the community. From the “I” to the “we.” You don’t just do an e.e. cummings where the “I” becomes a small “I,” the quiet voice within a larger arena. You want to get away from that “I” and join up with a communal voice.

Materialists make a million quests that we’ve been sold in this life, which is actually a betrayal of that communal spirit. They promote individualism and consumerism and turn the spiritual into an asset, once again, to be captured as some kind of end of the rainbow thing. An individual thing. And it robs you of your community wealth. Yes, there’s an individual voice. You raise your voice, and you sing together in a chorus, but it’s only because of the chorus that your individuality makes sense.

Michael Smith, a Jamaican poet, who died horribly young, had an argument against Western materialism. What he didn’t want was for Black people’s particular history to be put into a Marxian analysis so he’d say, “I don’t believe in socialism. I believe in social living.” He deliberately takes that term and gives it an onomatopoeic shift and communal basis. Smith is saying that class analysis does not look after race, gender, trans bodies, mental illness, police state, and prison industrial complex. You have to have a lot of other things come into play.

Another one for me is this idea of privatized imagination. It has been privatized by grants, by the individual rewards for individual books, by individual authors, and so on. The whole idea of the book and how it’s put together, the poems in there, it’s always about community. There is always a mother figure, a grandmother figure, or other people who are helping the poet make sense, helping the poem along, helping the play, the painting. It’s rarely an individual enterprise and that’s the weird thing about it. The whole enterprise of making a poem work is dragging stuff into it. It’s about a communal multiplicity. I think we should go back to reading our own poems and paying attention to their multivocal nature, noticing every single voice.

Shanta Lee Gander: You talked about the contract we have as poets, writers, and creatives to and with history. I would love to know: what would you say is our contract right now especially as poets, writers, and creators in the world? What is our contract with history?

Fred D’Aguiar: The contract is partly involuntary. As you know, we’ve come through a really painful reality, especially in the last couple of years. There’s nothing worse than realizing history isn’t yesterday, it’s now. And then you realize that Ahmaud Arbery’s death—he was actually hunted and shot in daylight by three people. It’s only because one of them videoed it that we have the outcome we have, which is a kind of justice, but not really justice because he’s dead. But that they [the perpetrators] have been brought to book.

With the death of Breonna Taylor, she was killed in her bedroom. There’s nothing worse than dying in your sleep. There’s something about that that is historically bound to the Black body, where one can be killed as they are dreaming. Maybe it’s even worse to have a slow, gradual lynching of George Floyd, on film, in broad daylight as we saw, with that long nine minutes and 29 seconds.

All of that tells me history had better be the thing instructing areas of your imagination as a writer because there it is, all around you every day, informing, circumscribing space and time.

So, I think in terms of the historical imagination, the contract is involuntary. It’s a must. Even as you pick up the pen, you better have a reason, even as you look at a material reality that’s brutal. The second you ask a question in the now, you have to go back in time. You have to see the way in which the city was redlined against Black mortgages. How the police go out and hunt for Black people to criminalize them. The way the prison system works to profit off Black bodies. The history is there.

I am also thinking about the Sankofa bird, a Ghanaian concept. The bird is flying, and it’s got an egg on its back. It’s looking back at the egg taking care of it as it moves forward. And the instruction is: to go forward, you have to look back and understand where you’re coming from. But there’s something organic about it because the egg is about the young that the bird is looking after. The egg that it takes care of implies that the future is only possible because of that egg’s preservation.

This also tells us that there is a pivot between the forward lean towards the future, the backward glance towards the past. And that’s all wrapped up in the present.

It’s an interesting thing because I know, right in us, there is this tug between Afropessimism and Afrofuturism. Afropessimism is the idea that if you look at American history closely, then you don’t see any evidence for investing in it because it’s all about the desecration and elimination of Black bodies, exploitation of Black bodies, profiting off Blackness, and so forth. On the whole, it’s about using up Blackness to preserve a white design system from its legality to its economics.

I think there’s a lot of truth in that, but I don’t think that’s the whole story because I don’t think the system is a forever system. The other side of it is Afrofuturism. The idea that if you imagine a future with Black people in it, you design a future that will preserve Blackness and make sure it exists. So, you begin to change the system just by looking at its trajectory and making sure you put yourself forward and your children. The egg on the back slingshots into that future.

We get more from both, and there are days when I feel pessimistically inclined, and I see it as a truth. But what keeps me writing is this belief that we have come back to a kind of civil rights era where we need to regroup and reorganize.

It’s a long answer, but I’m trying to tie in historical imagination with an awareness of a current political situation. They can’t be dissected or pulled apart.

Shanta Lee Gander: What advice do you have for writers seeking to pay attention to their radicles as they appear in their creative lives?

Fred D’Aguiar: Be a good listener before you say something. As a listener of people and their movements, you are not just watching—because watching is being a watchman or watchperson—but listening actively. It is about contemplating and thinking as you hear something without responding immediately.

I tell new writers to practice listening, which is about practicing stillness. I think it helps them hear currents in their own body and mental rhythms that they’re not aware of. Tones. Inflections. As you listen to what’s coming in and listen to what’s going out, the inside-outside division is broken down. Be a listener as well as a reader.

Read & Listen to “Jean ‘Binta’ Breeze (1956-2021)