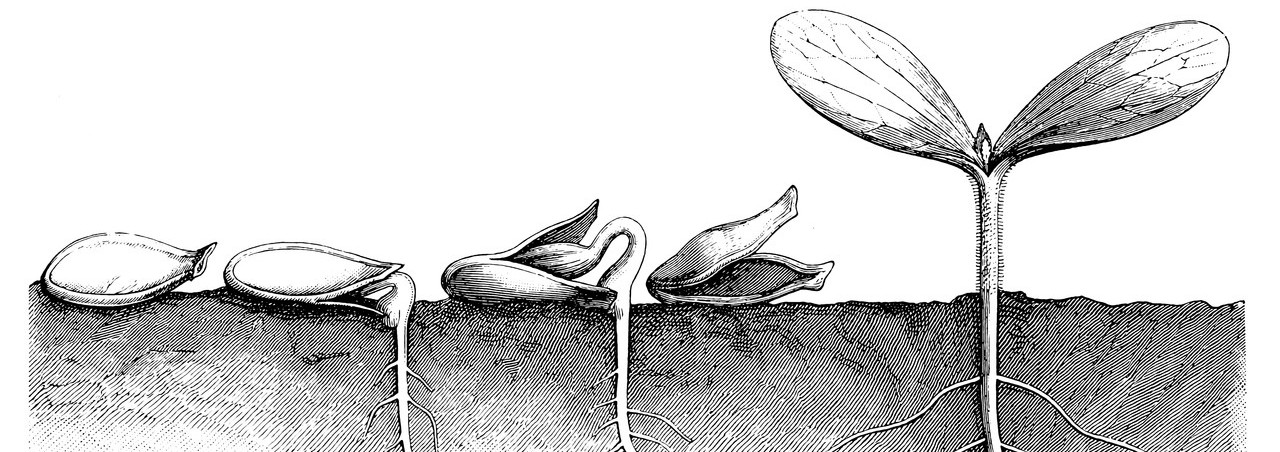

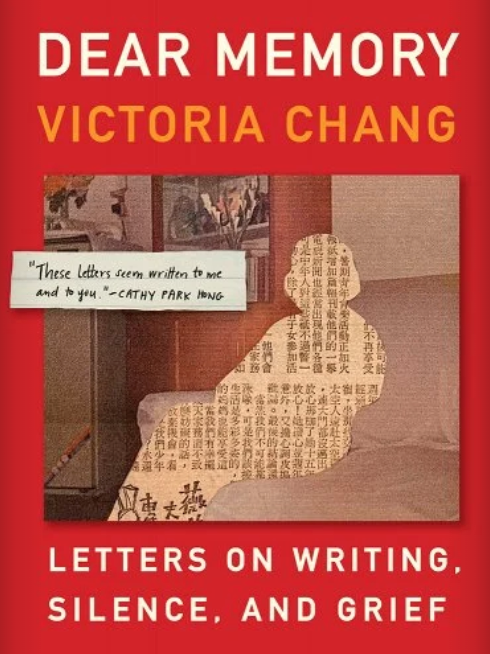

In Dear Memory: Letters on Writing, Silence, and Grief, a collection of 30 letters, Victoria Chang writes about intergenerational memory, silence, grief, racism, and death. Extending an approach featured in her poetry collection, OBIT (2020), she writes to both the living and the dead, as well as to concepts such as silence and longing. “Dear Silence, how do I enter you, seeking answers, but come out writing into and toward ambiguity?” Chang uses a multimedia, genre-bending approach to her first published book of prose by weaving together threads of letters, photos, altered images, poems, and intertextual dialogue with other authors.

The book appears as a combined photo album and letter collection. Between every prose segment, Chang includes images with poems superimposed on them. Some visual elements feature sparse information gleaned from a single interview with her mother conducted years before her mother’s death. She fills in windowpanes and sails on a ship with Chinese characters and writes poems on scraps of notebook paper cut into pieces of phrases or single words.

Chang wants to know her origin story, yet gaps and silences remain both wide and deep. A key thread in the book’s tapestry includes letters to family members, where she questions her deceased relatives regarding basic information about their lives, such as their birthdays, marriages, and migration from China to the United States. The most poignant letters include those to her mother, for whom she aches with loss. She notes, “Most people probably wonder why I am still writing about my mother. I want to tell them that it is because my mother is still dead.”

Another thread includes living former classmates and acquaintances identified by single initials, those who caused shame about the shape of her eyes, her fake jewelry, her athletic ineptitude. They reinforced her sense of otherness. She combatted their mistreatment with silence and achievement.

Unlike her family members who remained silent, and peers who exacerbated her loneliness, Chang’s teachers from elementary through graduate school fueled her growth and self-awareness. She writes to former teachers, reflecting rare positive influences and experiences. They gave her voice and agency; they encouraged her, unlike most other people she encountered.

Dear Memory is both timely and urgent, as contemporary domestic and international public health crises and political conflicts exacerbate the long arc of systemic racism and oppression. In this context, Chang’s reflections sharpen our awareness of how such forces can negatively affect an individual and a family for generations.

Words and poetry sustained Chang, served as a counterbalance to the shame and insecurity she felt as a child into adulthood. “The language of poetry reminded me to stay alive. It reminded me that, when it felt like I had nothing, I was nothing, I still had words.” She thanks the teachers in these passages and shares with them how she grew since their words first acted as buoys. In one letter to a teacher, she muses, “I felt that we each had our own unique stories and that stories could teach us how to begin to unpack the inner wordless experiences we all have.”

Throughout the text, she engages with other authors, absorbing lessons from their words. “I love when [Jeannette] Winterson says that the best work speaks intimately to you even though it has been consciously made to speak intimately to thousands of others.” If Chang aims to communicate with others by appearing to address to a single reader, she has succeeded.

Partway through the book, Chang pivots away from writing to deceased relatives and toward living family members who either cannot respond (her father became mute after a stroke) or who do not (her daughters with whom she may not have shared her thoughts and questions, given their young ages). She admits to her daughter, “I have spent a lifetime believing that the main thing that mattered was being smart. I have spent your lifetime, just twelve years, finding an exit from this corridor.”

Chang engages masterfully in meta-writing or writing about writing. She illustrates her drive for, experience of, and evolution of words on the page as she developed into a writer. She wanted to “write poems so I could make someone feel something,” and acknowledges writing as identity-making.

Chang explains her approach in the text for the final chapter, titled “Dear Reader,” in which she recognizes her use of the epistolary form to speak to people and objects that cannot or will not respond. She realizes she did not transcribe her memories, instead she sculpted them. “I take small fragments of imagery, memory, silence, and thought, and shape them with imaginary hands into something different.” She questions whether her memories are her own or amalgamations of memories and stories from others.

Like many great works of nonfiction, Dear Memory defies a simple characterization. One cannot overstate the resonance of Chang’s laser-focused journey into the core of some of the most vexing and heartbreaking yet unanswerable questions that humans face. Her words serve as a reminder that we continue to learn until we draw our final breaths. “By the time we die, we know everything we need to know.” One imagines Chang will continue to write into the silence and chisel away at words, so long as her memories evolve.

Available at Bookshop.

Kara Zivin

Kara earned her PhD and MS at Harvard University, her MA and BA at Johns Hopkins University, and her MFA at Vermont College of Fine Arts. She is Professor of Psychiatry, Obstetrics and Gynecology, and Health Management and Policy at the University of Michigan; Research Career Scientist at the Department of Veterans Affairs; and Senior Health Researcher at Mathematica, located in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Dr. Zivin aims to increase public awareness about and influence policy addressing behavioral health conditions by combining research expertise (data) and personal narrative (story). You can find her online at https://karazivin.com/